Why Ghana’s first lithium mine has yet to break ground after two years

The agreement, between the government and Atlantic Lithium through its local subsidiary Barari DV, was sealed on October 20th, 2023. Yet mining is still on hold, awaiting parliamentary ratification.

Two years after Ghana signed what it hailed as a landmark lithium deal, not a single tonne has been mined.

The agreement, between the government and Atlantic Lithium through its local subsidiary Barari DV, was sealed on October 20th, 2023. Yet mining is still on hold, awaiting parliamentary ratification.

Through the Africa Extractives Media Fellowship (AEMF), led by Newswire Africa and the Australian High Commission, Atlantic Lithium’s General Manager for Operations, Ahmed-Salim Adam, shared an update on the project and its uncertain path to production.

Ratification was expected in mid-2024. But political gridlock stalled the process. The opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) questioned the terms of the lease, and when Parliament stopped sitting in October 2024 over disputes about vacant seats, the process froze entirely.

After the December 2024 elections, the NDC won power.

Given the party’s earlier criticisms that the agreement was not in Ghana’s best interest, the deal now faces revisions under the new Lands and Natural Resources Minister, Armah-Kofi Buah.

When the lease was first signed, the government hailed it as a breakthrough. Officials touted it as Ghana’s best mining agreement yet, and even one of the strongest in Africa.

The deal promised a 10% royalty rate, notably higher than the country’s usual 5%.

Ghana’s Minerals and Mining Act of 2006 had pegged royalties between 3% and 6%, but a 2015 amendment scrapped that range and gave the minister discretion to determine the rate.

The mining lease also required that 1% of total revenue, not profit, go into a community development fund for affected areas. In addition, the government secured a 13% free carried interest, alongside ground rent, a growth and sustainability levy, mineral rights fees and a 35% corporate income tax.

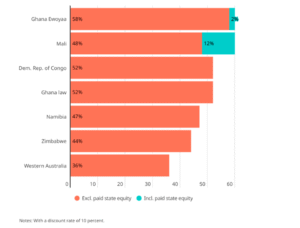

The Natural Resource Governance Institute estimated Ghana’s effective tax take at 58%, higher than in most lithium-producing countries.

To the previous administration, this was a triumph.

The NDC, however, thought otherwise. On December 13th, 2023, the party’s communications officer, now head of the Ghana Gold Board, Sammy Gyamfi, declared that the deal “was not in the best interest of Ghana.”

The opposition at the time argued that the 10% royalty should be a minimum, with room to rise as profitability improved. They also faulted the lease for failing to guarantee joint ventures that would ensure local participation.

While the lease required a feasibility study on setting up a processing plant in Ghana, it did not make domestic processing explicitly mandatory.

Ahmed-Salim confirmed that the company had concluded and submitted the results of the study and found the plant commercially unviable, citing the absence of a local value chain, inadequate infrastructure and the limited production volumes expected from Atlantic’s Ewoyaa mine.

“We would need about three Ewoyaa mines to make it feasible,” he said, adding that such a plant could make sense only if more lithium producers entered the field or if the government introduced generous subsidies.

Civil society groups echoed some of these concerns, arguing that Ghana’s lithium potential would bring little value if the country remained a mere exporter of raw minerals.

It is now almost certain that the NDC government will amend the lease before presenting it to Parliament.

In its 3rd quarter update released on October 31st, Atlantic Lithium said it had concluded negotiations with the government and is now awaiting Cabinet and parliamentary approval.

A new challenge has since emerged: falling lithium prices.

When the lease was signed in 2023, Atlantic Lithium had based its profitability on a benchmark of about $1,500 per metric tonne. Prices then hovered near $2,800. By 2024 they had crashed to between $700 and $800, reflecting a glut in global supply.

Today, the price sits around $944 per tonne.

Facing thinner margins, Atlantic Lithium has asked the new government to lower the royalty rate to Ghana’s standard 5% and to offer other incentives.

The company argues that it continues to bear costs despite the delay in ratification, maintaining community programmes and paying mineral rights fees.

Ahmed-Salim disclosed that management salaries were cut and over 100 staff were laid off to contain losses.

Experts, however, urge caution.

The Natural Resource Governance Institute says the government should rigorously test Atlantic Lithium’s assumptions before granting any concessions.

Its analysis suggests the project may remain profitable even at current prices.

The Institute warns that approving permanent tax cuts could set a precedent for other mining firms, and that any relief should be temporary or tied to a sliding scale that adjusts as prices recover.

Still, in 2024, the company was lobbying hard for ratification even as prices fell. Now, with a mild rebound in sight, optimism has returned and a permanent cut in the royalty rate would be harder to defend.

Analysts at J.P. Morgan expect prices to rise to between $1,100 and $1,300 per tonne, possibly reaching $1,500 if supply tightens and electric-vehicle demand keeps climbing.

The outlook remains cautiously positive, barring any major geopolitical shocks.

Lands Minister Armah-Kofi Buah has hinted that he will soon present the revised lease to Parliament but has given no details about the amendments.

If the government reduces the royalty to a fixed 5%, it may forfeit potential windfalls should prices recover. The risk is complicated by Elevra Lithium (formerly Piedmont Lithium), which owns 40% of the project and is set to buy half of Ewoyaa’s production.

A sliding royalty scale tied to market prices would be difficult to enforce, since the company could underprice its own offtake unless a transparent benchmark is established.

Some civil-society groups have also questioned Atlantic Lithium’s financial capacity and experience, arguing that its push for revised terms reflects balance-sheet strain as much as project economics.

The point is not far-fetched. The delay in ratification has already forced the company to cut staff and scale back operations, while weak lithium prices have squeezed margins.

Atlantic’s latest quarterly report also notes a dispute with Elevra, formerly Piedmont Lithium, over how development costs should be shared under the joint-venture agreement.

The disagreement has shifted more of the near-term funding burden onto Atlantic, adding to the pressure created by low prices and regulatory delays.

The firm, for its part, insists it still enjoys backing from its partners.

From Ahmed-Salim’s comments, Atlantic Lithium remains eager to begin mining with its partners. However, he confirmed that the final investment decision will depend entirely on the contents of the amended lease and investor sentiment after ratification.

The new government faces a delicate balance.

It must pursue value addition, local participation and greater state benefit without undermining investor confidence. The previous administration was criticised for limited consultation before signing the 2023 lease. The new one must avoid repeating that mistake and engage civil society and the public before final approval.

The earlier government also announced a green minerals policy but never published it. Making that policy public could guide investor expectations and reassure citizens that Ghana’s mineral wealth will be managed transparently.

For now, Atlantic Lithium must keep spending to hold its concessions and sustain goodwill with communities while reassuring investors that Ghana remains a viable destination.

That is no small challenge.

In recent years Ivory Coast has drawn more mining investment than Ghana, helped by steadier policies and faster approvals. Ghana’s new administration must therefore tread carefully.

The revised lease will show whether the government can turn its talk of value addition and higher revenue into the predictability investors expect.

How both sides manage that balance will determine not only the fate of Ghana’s first lithium mine but also its standing in the global contest for green minerals and scarce capital.